India gives a whole new meaning to diversity. The vast country has at least 15 major languages, hundreds of dialects, several major religions and thousands of tribes, castes and sub-castes.

A Tamil-speaking Brahmin from the south shares little with a Sikh from Punjab — each has his own language, religion, ethnicity, tradition and mode of life.

So it makes you wonder, how realistic is the contention from economic observers that, by 2022, growth will create one urban middle class whose interests transcend region, caste, religion…? What will India look like by 2022, and what opportunities and challenges will investors encounter?

“India will continue to remain an attractive investment destination, more so since there seems to be a lot more stability on the central government front,” says Sunil Hansraj, Chandabhoy & Jassoobhoy & Affiliates, one of UHY’s two member firms covering India. “With the new government having come to power in May last year, there was an expectation of ‘big ticket’ reforms and policy announcements which, though not seen as yet, are expected to be put in place steadily over the next six to eight months.

“The government is placing great emphasis on reviving manufacturing and increasing investment in infrastructure, which are expected to put the economy back on track and boost growth. Industry is cautiously optimistic on this front and many large corporate houses are already seeking to increase their investments.”

Cities: the place of wealth

Most of India’s wealth is already generated from its cities and towns. Urban India accounts for almost 70 per cent of the country’s GDP. But almost 70

per cent of its people still live in rural India. As a consequence, for politicians, the cities have primarily become a place of wealth, development and tax generation, while the countryside is predominantly their place of legitimacy and power. The countryside is where the vote is; the cities are where the money is.

But, by 2022, the Indian government aims to have economically empowered 580 million of the 680 million currently unable to meet basic needs, creating a greater sense of united nationalism than ever before.

Economic liberalisation, say observers, will have created one national economy; technology will have created one national culture. As India grows its global awareness, by 2022 its people will be celebrating what distinguishes them from other Asian countries (rather than from each other) — and that will bind them together as one united nation.

Where are the investment opportunities?

It’s tempting to think that future investment opportunities have the most potential in ‘Urban India’ and among the new urban middle class. They do, of course, but opportunities also abound in government and state contracts supporting the administration’s bid to ensure poverty is finally in retreat.

India launched its first wave of economic reforms in the early 1990s, resulting in a decline in the official poverty ratio from 45 per cent in 1994 to 37 per cent in 2005. Over the next seven years, a period in which India achieved the fastest rate of economic growth in its history and also implemented policies aimed at helping the poor, extreme poverty declined rapidly to 22 per cent of the population, or some 270 million people. Now the government has set still higher aspirations: more than half a billion people are to be supported as they build a more economically empowered lifestyle.

Policy-makers at all levels of government, both national and state, are focusing on an agenda that emphasises job creation, growth-oriented investment, farm sector productivity and more innovative delivery of social programmes. While the framework and funding would fall to central government, many of the specific initiatives that will make this agenda a reality will be implemented at state level.

Products and services providing access to clean cooking fuel and electricity for lighting needs are in demand. Efficient sanitary latrines in rural households, and underground sewerage with wastewater treatment in urban households, are needed to cope with wastage and leakage. Primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare services are being identified, as are services in primary and secondary education (particularly vocational training).

Effective governance and supply chain control is also a priority. The government estimates that, on average, Indians lack access to 46 per cent of the services they need and, significantly, just 50 per cent of government spending actually reaches the people it is intended to reach — much of it is lost to inefficiency or corruption. During 2005–2012, 35 per cent of India’s food subsidy, for example, did not reach consumers, and the poorest population segments received less than 40 per cent of the subsidy intended for them.

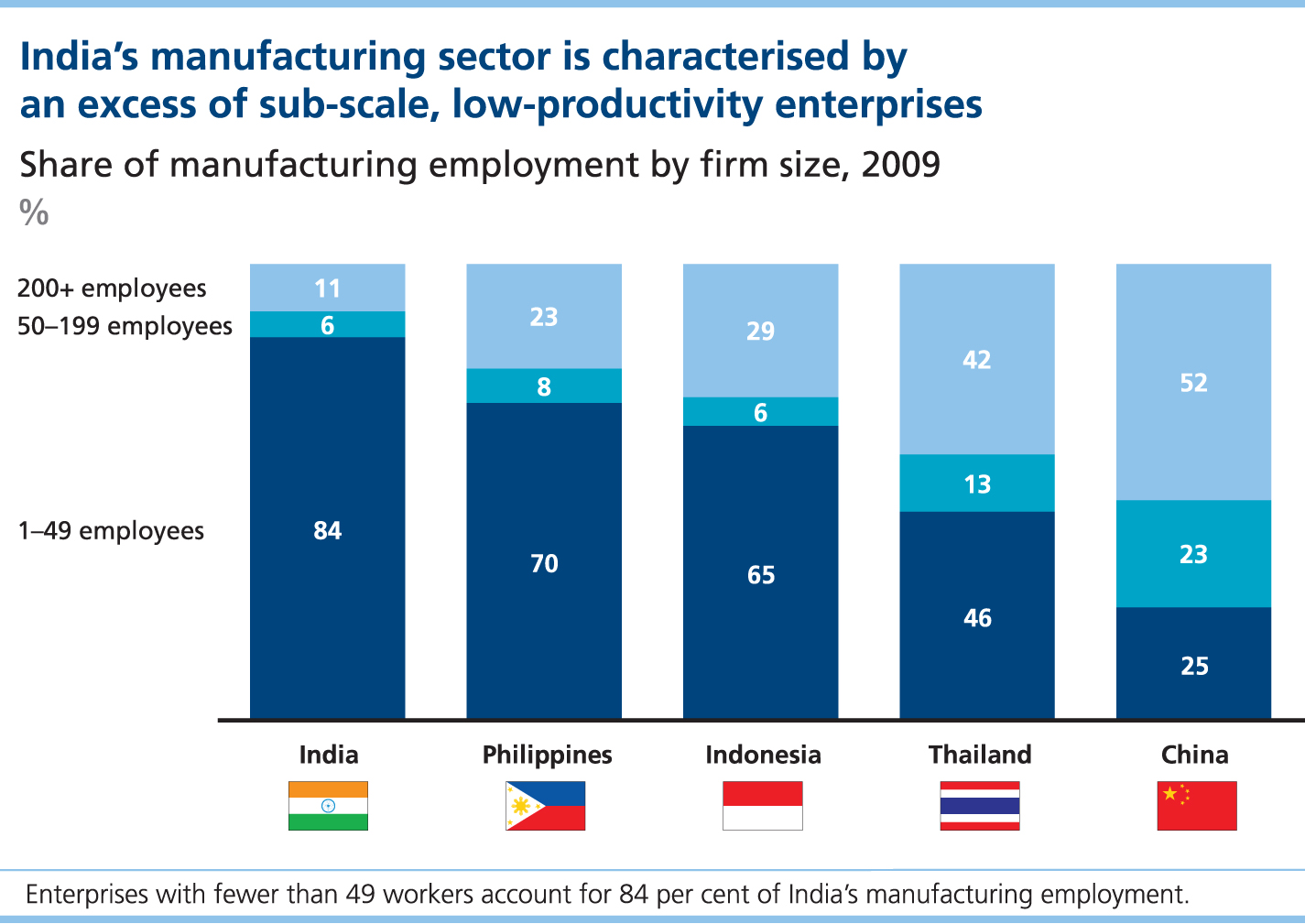

India’s manufacturing sector is characterised by an excess of sub-scale, low-productivity enterprises

Share of manufacturing employment by firm size, 2009

%

There are too few job opportunities outside the farm sector, a factor that limits the economic opportunities available to women in particular. In fact, just 57 per cent of India’s working-age population participates in the labour force — well below the norm of 65 to 70 per cent in other developing countries.

India’s labour productivity also lags because of the high prevalence of poorly organised and sub-scale businesses. Enterprises with fewer than 49 workers accounted for 84 per cent of India’s manufacturing employment in 2009, compared with 70 per cent in the Philippines, 46 per cent in Thailand and just 25 per cent in China. Micro enterprises in India, across both manufacturing and services, typically have just one-eighth the productivity of larger enterprises with more than 200 workers.

Focusing on productivity of the agricultural sector to lift the incomes of smallholder farmers is one of the most direct routes to addressing rural poverty. Yet, agriculture has not kept pace with growth in India’s broader economy. Today the nation’s yield per hectare is half the average of China, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand.

Moreover, in the past, government spending on agriculture has focused on input and output price support rather than investment in agricultural infrastructure, scientific research and extension services (which educate farmers on new technologies and best practices). In 2010–11, the government spent Rs. 86,000 crore (USD 18 billion) on input subsidies (primarily fertiliser), but less than half that amount, (Rs. 34,000 crore, or USD 7 billion), on building storage and irrigation systems, as well as scientific research and extension services.

Source: Asian Development Bank, Key indicators for Asia and the Pacific.

Dream versus reality

But… is all this for real? India has a bumpy track record of economic reform and achievement. Are government empowerment targets achievable, or are they just a pipedream? The answer, predictably, lies somewhere in between.

When you explore the outcomes of strong economic growth over the past 20 years, matched by economic reforms (albeit currently stalled), the reality is that India has already started to transform itself. The Indian middle class now numbers more than 250 million and more than 30 per cent of the 1.2 billion population already lives in urban areas. These numbers are growing fast (fuelled not in small part by Indian movies featuring young, aspiring people filled with idealism and ambition).

Unusual in combining the growth of an emerging market with the openness of a free-wheeling democracy, India has also thrived on an information explosion, boasting more than 170 television news channels in dozens of languages. Three-quarters of the population have mobile phones.

Globalisation has raised expectations for this new urban middle class. Whereas once it was assumed that to get rich you needed political connections, today you can simply dare to have good ideas and work hard.

The Aadhaar programme (aadhaar means ‘foundation’ in Hindi), spearheaded by India’s tech pioneer Nandan Nilekani, is giving every Indian a unique biometric identity, aimed at making it possible for them to get their rights and benefits without middlemen, corruption or state inefficiency blocking their path. The programme, say observers, will enable Indians to think of themselves, for the first time, not only as members of a religion, caste or tribe — but as individuals.

Yet… India’s economic engine has been spluttering since 2011 and there has been a growing sense of legislative and administrative paralysis. In a scenario of stalled reform, the contrary view raises its head — that poverty will likely maintain its grip on a large section of India’s population; that, in the absence of major reforms, India’s GDP will grow at just 5.5 per cent from 2012 to 2022; and that, sadly, the effectiveness of government social spending will remain unchanged.

What’s needed to make the difference

For the government to reach its transformation targets, McKinsey & Company researchers estimate that India needs 115 million new non-farm jobs over the next decade to accommodate a growing population. India’s industrial sector will need to lead the way on job creation, especially in construction and manufacturing. These sectors can absorb lower-skilled labour moving out of farm jobs. Labour-intensive services — such as tourism, hospitality, retail trade and transportation — will need to add 35 million to 40 million jobs.

Almost half of the required jobs will need to be generated in states with difficult starting conditions (such as challenges with the quality of education, which exacerbate skills shortages). Uttar Pradesh’s labour force, for example, say researchers, will need some 23 million non-farm jobs (approximately one-fifth of the national requirement) — even though the state is largely rural and organised enterprises currently account for only 9 per cent of its employment. Some 11 million workers from the state of Bihar will need to be absorbed into the non-farm sector in an even less advantageous climate. “India’s job-creation strategy must provide broad-based reforms that invigorate job growth, both in these regions and across the entire country,” say the researchers.

“As China moves up the value chain, India and other emerging economies with low labour costs have an opportunity to capture a larger share of labour-intensive industries by integrating domestic manufacturing with global supply chains. But an array of barriers limits the ability of Indian businesses — both large and small — to invest and become more competitive, scale up and create jobs.”

Revitalising India’s job-creation engine will require decisive priority reforms, say researchers:

India needs to accelerate critical infrastructure for power and logistics Infrastructure gaps, especially in power and transportation, hinder economic growth, particularly in manufacturing.

The administrative burden on businesses needs to be reduced Complex and archaic regulations pose a significant cost, especially for micro, small and medium-sized businesses, discouraging both investment and their move into the formal economy.

Government services should be selectively outsourced to private-sector providers

The roll-out of ‘one-stop shops’, supported by automated government processes, can be accelerated through outsourcing.

Tax distortions need to be reformed India’s many taxes result in high compliance costs, and differences across states and sectors balkanise the national market, harming the ability of businesses to achieve economies of scale. The proposed goods and services tax, a harmonised consumption tax across nearly all goods and services, represents a step towards reducing complexity and lowering the tax burden.

“The goods and services tax is still work in progress, though the government seems to be making reasonable progress in discussions with the states,” says Sunil Hansraj. “The next four to six months could give us a clear indication of how and when the tax regime would be implemented.”

Land markets need to be rationalised In 2013, India enacted the Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Bill, which was intended to create a framework to deal fairly with the displaced. However, inefficient land markets remain a major impediment to economic growth, as property rights are sometimes unclear and the process for land acquisition is time-consuming. India can reinforce property rights by demarcating land holdings through geospatial surveys and provide standardised title to landowners through digitising records.

Labour markets need to be more flexible

At least 43 national laws — and many more state laws — create rigid operating conditions and discourage growth in labour-intensive industries. But, ironically, they secure rights for only a tiny minority of workers. A multitude of rules that restrict terms of work and work conditions should be simplified or eliminated. In the medium term, India could rationalise laws governing dismissal, pairing this with measures to reinforce income security for the unemployed.

Government-funded mechanisms need to help poor workers build skills Vocational education is needed most acutely by the poorest workers — those with little or no education and those who live in rural areas. There are 278 million Indians of working age in these categories, but they are underserved.

.