Mexico is an economy in transition. It will take a generation or more for the transition to become complete. But, make no mistake, Mexico is on the move, empowered not just by large modern firms but small to medium-sized (SME) traditional businesses that are stepping up to take advantage of economic growth.

To date, transition among SMEs has been hard to find. But in pockets of enterprise, slowly but surely, they are benefiting from fiscal reform and professional support — and moving forward into a new Mexican era of increased effectiveness, productivity and international competition.

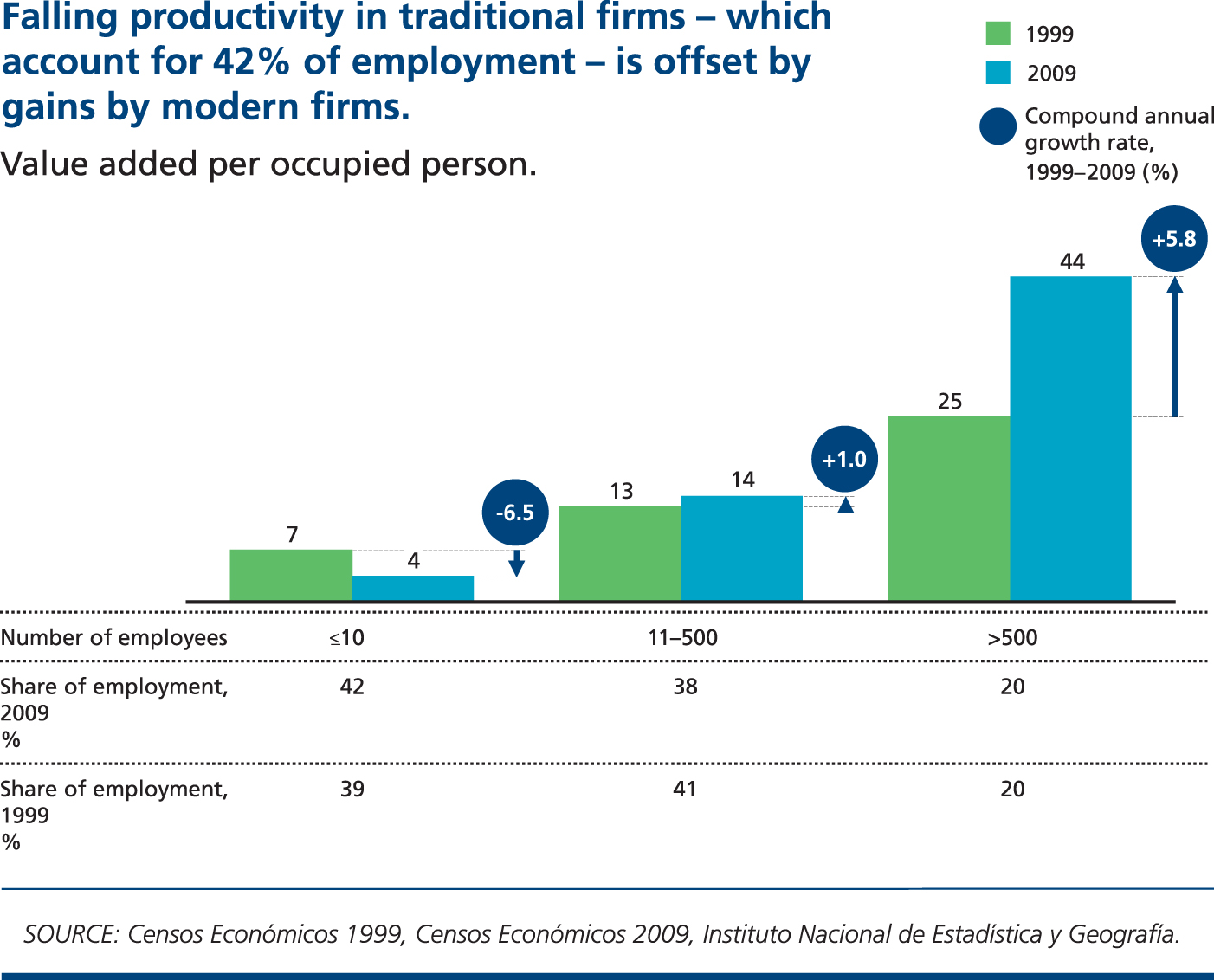

Research by the McKinsey Global Institute points to the long haul ahead. Productivity has grown by 5.8% a year in large, modern Mexican firms, but has fallen by 6.5% a year in traditional firms. In 1999, small traditional firms were 28% as productive as large modern ones, but by 2009 they were only 8% as productive.

For example, the 0.5 per cent of baking-industry employees who work in the very large, best-in-class corporates generate half of the industry’s added value. The vast majority of baking employees, however, work in traditional neighbourhood panaderías (bakeries) and tortillerías (small-scale tortilla factories), which achieve just one-fiftieth of the productivity of the best-in-class, large bakeries.

These ‘old versus new’ businesses reflect the dualistic nature of the Mexican economy as a whole. On one hand, ‘modern Mexico’ is a high-speed, sophisticated economy with cutting-edge auto and aerospace factories, multinationals that compete in global markets and universities that graduate more engineers than Germany.

In fact, Mexico has become one of the world’s top five auto producers. Annual production at the 10 largest Mexican plants rose from 1.1 million vehicles in 1994 to nearly 2.9 million in 2012. Many Mexican plants are regarded as world-class; some exceed average US productivity levels.

In food processing, Mexico’s Grupo Bimbo is a highly automated global player that has become the world’s largest baking company, with modern-format stores adopting the latest supply-chain management practices.

By comparison, ‘traditional Mexico’ is small-scale, low-speed, technologically backward and unproductive, often operating outside the formal economy (thereby avoiding taxes and other business costs).

What makes this gap frustrating, is that, so far, three decades of government economic reforms have failed to boost the country’s GDP growth.

Without capital to invest in new technology, the traditional sector has relied on manpower and a rising share of employment, creating jobs at a faster rate than the modern economy — the opposite of what typically happens as economies develop. Hence, GDP growth has stagnated. It fell to 1.1 per cent in 2013 (compared with annual average growth of 4.3 per cent between 2010 and 2012). Deceleration was driven by weaker export demand and a contraction in domestic investment, according to the World Bank.

Mexico’s GDP per capita has been similarly weak, rising by just 0.6 per cent per year on average (only 0.4 per cent during 2013) because of weak labour productivity, which fell from USD 18.30 per worker per hour (in purchasing power parity) in 1981 to USD 17.90 in 2012.

Key reforms for growth

Yet, the government – working towards mid-term elections in July 2015 – is pursuing with determination reforms in areas such as labour market regulation, education, telecommunications, financial sector regulations… The World Bank predicts a gradual recovery over the next few years, with more dynamic exports as the US economy gains pace, propelling economic growth back to the range of 3-4 per cent. Private investment, particularly in the liberalised energy sector, is expected to be key in enhancing economic growth.

Financial reforms, meanwhile, are aimed at promoting higher lending, particularly to SMEs at lower rates through development banks – to counteract Mexico’s low credit-to-GDP ratio, which lags far behind international standards. The reforms are designed to:

• Increase the role of development banks

• Encourage more lending by private sector banks

• Increase competition among commercial banks

• Strengthen the stability of the financial system.

Currently, in a Central Bank of Mexico survey, more than 80 per cent of Mexico’s capital-starved SMEs quote their credit sources as ‘suppliers’ (suggesting informal arrangements) rather than banks. Research shows that an important determinant of access to formal credit is to have had that access before – which automatically excludes firms with no credit history. The World Bank estimates that, as a result, more than half of Mexico’s SMEs have insufficient access to financial services.

Government reform of development bank support is aimed at increasing financial inclusion for smaller businesses. The government’s finance minister has given examples of how development banks could be utilised. One example is a guarantee by a development bank to underwrite commercial banks that give credit to firms with no credit history. According to the Ministry of Finance, in just one month the programme supported 6,000 firms.

Increasing credit to firms, particularly SMEs, will increase growth through more investment and through more consumption, creating a virtuous circle between credit and economic growth in Mexico, says Bank of America Merrill Lynch, welcoming the moves. However, for development bank credit to fuel growth, loans need to be directed to projects that create more jobs – projects created through SMEs that create about 70% of total employment.

Till now, however, government reforms have been enthusiastically adopted by modern businesses, many with global ambitions, but have barely touched ‘the other Mexico’, where traditional enterprises have operated in ‘the same old ways’, informality has risen, and productivity has been plunging, says McKinsey Global Institute. Overall, the productivity gains of modern companies have been all but offset by the decline in traditional businesses, leaving economy-wide productivity growth at about 0.8 per cent a year since 1990.

“For Mexico to get closer to its pre-1980 buoyant GDP growth rates, raise per capita income, grow the middle class, and bring more people out of poverty… the government must find a way of narrowing the gap between the ‘two Mexicos’ “, says McKinsey Global Institute.

Policies and practices that discourage traditional businesses from formalising in order to qualify for financing and invest in growth need to be rethought. More companies and workers need to move into the modern economy, creating a vibrant and globally competitive SME sector. More companies need professional support to grow and develop.

UHY’s member firm in Mexico, UHY Glassman Esquivel y Cía S.C., is at the forefront of supporting SMEs as they modernise. “We’re looking to create a business environment that encourages entrepreneurship and growth and removes economic barriers and short-sighted incentives, which, in the past, have encouraged businesses to remain small and informal,” says managing partner Oscar Gutiérrez Esquivel.

Falling productivity in traditional firms – which account for 42% of employment – is offset by gains by modern firms.

Value added per occupied person.

(Many companies have remained small and continued to operate informally because of these economic incentives. The regulatory cost of establishing and operating a formal enterprise in Mexico is relatively high, and enforcement is weak and too often tainted by corruption, enticing companies of all sizes to conduct all or part of their business beyond the strictures of the formal economy.)

“More viable regulatory enforcement would also help companies join the formal economy,” says Oscar Gutiérrez Esquivel. Currently, it costs twice as much (as a percentage of average income) to register a business in Mexico as in Chile — and seven times as much as in the US.

(Not only is it far costlier to start a formal business in Mexico than in peer countries, but it also costs more to expand: construction permits cost three times the average income per capita compared with 67 per cent in Chile. There are also wide variations in regulatory processes and regulations within Mexico: it takes six days to start a business in Monterrey and 49 days in Cancún.)

Despite reforms, requirements in Mexican labour regulations also discourage the hiring of full-time employees. Companies have limited flexibility to lay off workers or hire part-time employees. They must also contribute to profit-sharing plans.

To skirt these requirements, more and more employers are hiring even core personnel through contractors.

Broad measures needed to support growth across the Mexican economy include reducing electricity costs, upgrading infrastructure, improving labour-force skills and continuing to improve security. These ‘enablers’ will be important for continuing productivity improvements of modern and traditional companies alike — steps that are critical to reaching overall productivity goals.

How the two-speed economy came about

For three decades from the early 1950s, Mexico urbanised and industrialised at a rapid rate. GDP rose by an average of 6.5 per cent annually. From 1950 to 1970 productivity rose by 4.3 per cent a year on average. The ‘Mexican Miracle’ was hailed as a model for economic development.

That era passed, however, and growth has never fully recovered. An expansion of public spending under the ‘shared development’ programme in the 1970s led to financial imbalances that proved unsustainable when oil prices plunged, resulting in a financial crisis and devaluation in 1982.

Since 1981, GDP growth has averaged 2.3 per cent a year — mostly due to the expanding labour force — and GDP per capita has grown by just 0.6 per cent a year. Labour productivity, which fell sharply from its 1981 peak, has yet to recover completely in purchasing power terms. In 1980, Mexican GDP per capita was 12 times China’s GDP per capita. At current growth rates, China could surpass Mexico by 2018.

Volatile energy prices and financial crises have been part of the explanation, but stagnation among traditional enterprises, that limits GDP and productivity growth, has been at the heart of this malaise. Traditional enterprises employ 42 per cent of all workers, yet in 2009 contributed just 10 per cent of the total added value to the Mexican economy.

Lack of capital compels traditional companies to rely excessively on labour-intensive methods to raise output (often using family or informal workers), rather than making capital investments — thereby exacerbating the productivity problem. Lending in advanced economies, as a share of GDP, is 4.5 times higher than in Mexico. At 33 per cent of GDP, Mexico‘s lending places it behind Ethiopia, a nation with much lower GDP per capita.

To raise GDP growth to 3.5 per cent, the Central Bank of Mexico’s growth projection for 2014, productivity would need to rise by 2.3 per cent annually — almost three times the rate between 1990 and 2012. To meet the government’s 6 per cent goal would require raising productivity by 4.8 per cent annually, or about six times the rate of the past two decades.

Opportunities for increased productivity

“We see abundant opportunities to raise Mexican productivity to rates that would accelerate GDP growth,” says Oscar Gutiérrez Esquivel.

“Mexico has many of the ingredients in place for both productivity improvement and accelerated GDP growth. It has not stinted on investment — roughly one-quarter of its GDP goes into fixed capital investment, a rate that is among the highest in Latin America. And Mexico’s macroeconomic environment has become increasingly stable over the past decades.

“Mexico has adopted many important market-opening reforms that have enabled the success of highly productive modern companies. As these large private corporations have been exposed to global competition at home and have expanded abroad, they have sharpened their operating skills. Such success is being translated into the SME sector, creating a new middle layer of entrepreneurial businesses focused on growth.”

With professional support, such enterprises are introducing labour-saving equipment and improving basic business processes. “Some strategies, such as investing in productivity-improving equipment and technologies, may be beyond the reach of some traditional enterprises that lack scale and access to capital,” says Oscar Gutiérrez Esquivel. “However, companies of all sizes can introduce improvements such as adjusting product mix to include more high-value-added items. In addition, small enterprises can join buying consortia to qualify for discounts and gain access to better raw materials. In this way, for example, small bakers might raise quality and generate higher profits to invest in productivity-improving equipment.”

Food and beverage stores, the largest sub-segment of the retail industry, present an enormous opportunity for productivity improvement. Today, modern-format chains account for 65 per cent of sales. Yet traditional mom-and-pop stores, market stalls and counter stores continue to proliferate. They employ 84 per cent of workers in food and beverage retailing but have only 20 per cent of the productivity of modern stores. Many small stores have limited display space, requiring workers to take orders or suggest items to customers and fetch merchandise from storerooms, lengthening transaction times and hampering productivity.

“More small companies need to grow into modern mid-sized companies, and more mid-sized companies need to grow into large modern corporations,” says Oscar Gutiérrez Esquivel. “By helping traditional enterprises evolve into modern, formal SMEs, with appropriate government actions to make informality less attractive, assistance from the private sector, and efforts by small business owners, many of Mexico’s traditional enterprises can evolve into the new breed of modern companies in the new middle-sector, ‘middle way’ economy.”

.