There are many sound commercial reasons for small to medium sized enterprises to expand beyond their home market. European Commission director general for internal market, industry, entrepreneurship and SMEs, Istvan Nemeth, says that being internationally active links with higher turnover and employment growth, and there is a relationship between internationalisation and innovation.

To find out how companies successfully manage elements of internationalisation such as human resources, business culture, finance and logistics, we asked specialists for their views.

PEOPLE MATTER

Hiring local talent who can create the right brand and culture is important, as is understanding cultural diversity, says Kate Chapman, group HR director at recruitment firm PageGroup. “It is vital when exporting talent that they have a good understanding of the cultural nuances they will encounter.”

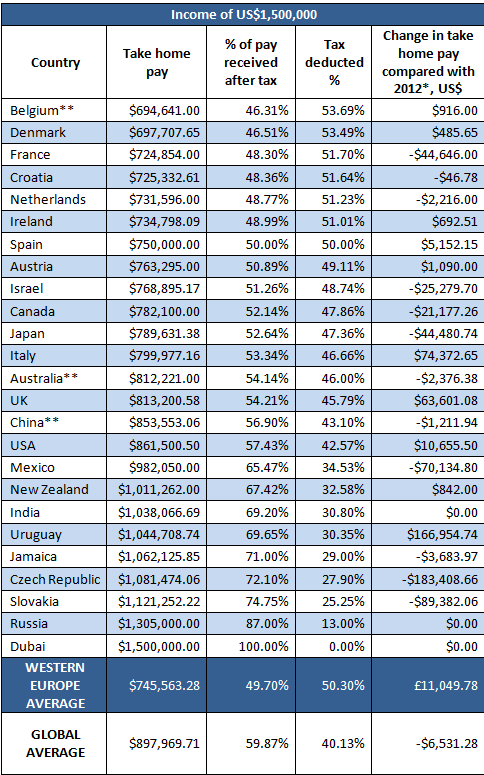

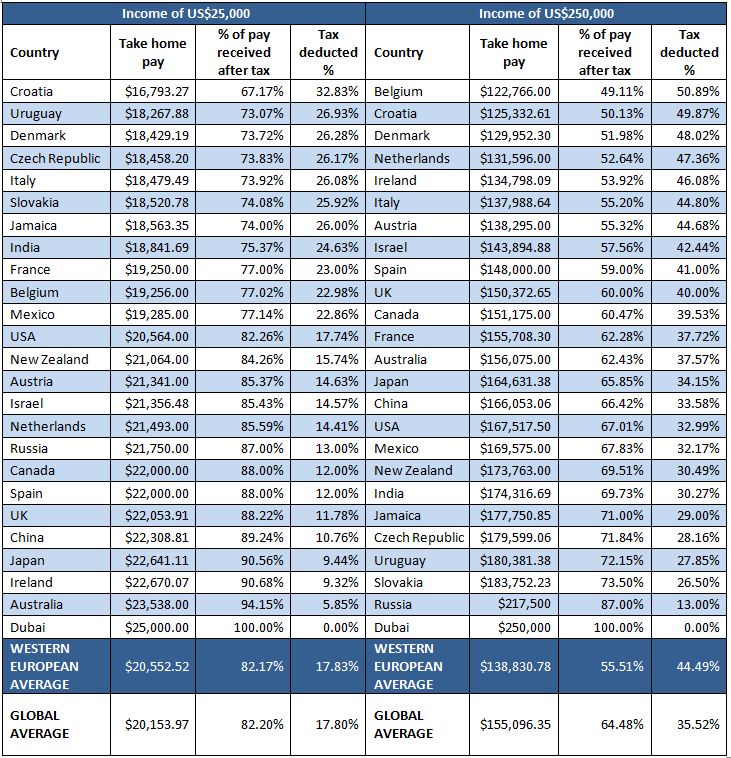

Kate says that for people moving abroad on an international assignment, it is not always about the money. “Expats may take advantage of lower tax rates but people relish the opportunity to experience life in a different culture,” she says. “Once many of our people move abroad they rarely go back to their host country, making multiple moves with us throughout their careers.”

CULTURAL NUANCES

Knowledge that prepares a business for new territory must be part of the decision to enter that market. But cultural research tends to be too general, stereotypical and out of date and may encourage a formulaic response to highly nuanced situations that can narrow the focus of leaders to that of following a process rather than ‘heads up’ flexibility and awareness.

That is the view of Malcolm Nicholson, coaching director at Aspecture and the UK representative for the Centre for International Business Coaching. He says businesses expanding internationally should be helping leaders to understand and develop their ability to juggle conflicting forces. “We are learning to work with more memberships of groups and feel part of them. Helping leaders integrate into new multicultural social and work environments is essential, at both personal performance and business levels.”

An inevitable by-product of having people in close proximity is some form of conflict, he says. “This is generally handled according to the law of the land, the culture of the

organisation and the manager’s discretion. Add regional culture to the mix and accepted norms vary significantly.”

MAKING MONEY COUNT

Finding a bank that offers services in multiple countries or regions can be a challenge for companies with revenues in the millions rather than billions, explains Bob Lyddon, general secretary of the International Banking Association. “There is a trend for banks to focus on doing business just in their ‘home’ market, which has thinned out the competition in international banking. Anti- money laundering and ‘know your customer’ requirements mean domestic banks are starting to shun foreign customers because of the difficulty of fulfilling requirements around identifying ultimate beneficial owners.”

If the applicant is a non-resident, someone at the bank has to examine papers issued in a foreign jurisdiction and attest that they prove the existence of the applicant and the bona fides of directors, signatories and owners. “The same applies where the applicant is a resident but with foreign ownership,” says Bob. “The result, if not a rejection, is an onerous process. It is much easier when the customer’s own bank has strong relationships with foreign banks, with agreed standards for responsiveness, timing and paperwork.”

Bob says the most important requirement for aspiring international business is access to people who can explain clearly the market practices in foreign jurisdictions and the most appropriate local payment and collection services.

KEEPING IT MOVING

According to Mark Parsons, chief customer officer UK & Ireland for DHL supply chain, three trends characterise the challenges and opportunities in emerging markets: regionalised supply chains, shortening product life cycles and shifting demographics.

Rapidly changing consumer behaviour, coupled with the variables of infrastructure, culture, regulatory and political regimes and economic development, make unpredictability the norm. Factor in limited talent pools, fragmented distribution systems and security concerns and the unknown variables grow.

“As one global networking products supplier put it, we are in markets now where we are not going to get the density and leverage to build economies of scale for five to ten years,” says Mark. “This is a problem for a lot of US and European companies that are used to having projects with a two-year payback.”

His colleague, head of DHL resilience team, Tobias Larsson, says corporate supply chain organisations are often siloed, operate on a regional basis and are disconnected among regions and even sites. “They lack visibility and control beyond their part of the operation. That may work day to day, but in crisis, it can be a problem.”

RISKY VENTURES

Companies with international ambitions must also take account of factors like currency volatility. Borrowing in local currency and managing working capital effectively can help reduce the impact of currency fluctuations. However, the increased currency risk when operating in emerging markets brings with it the need for clear, complete information about any risk being created.

Political instability is a consideration in many parts of the world. Poor governance, extreme levels of corruption and civil unrest are among the challenges facing international business operations in emerging markets, says Charlotte Ingham, principal political risk analyst at global risk analytics company Verisk Maplecroft.

Corruption not only undermines overall governance levels, but also serves as a key source of popular dissatisfaction. With nearly 70% of countries rated as ‘extreme’ or ‘high risk’ in Verisk Maplecroft’s corruption risk index and 41% similarly rated in the civil unrest index, widespread discontent is likely to remain a significant feature of the global political risk environment in the short term.

Exporters are also advised to protect themselves against late and non- payment. Because overseas customers will take longer to receive their goods than customers in a domestic market longer payment terms are inevitable. Exporters concerned about cashflow should consider asking suppliers for longer terms. For those worried about an overseas customer refusing to pay, credit insurance may be an option. Clearly defined contractual obligations are essential – exporters have to consider factors such as the currency of the contract and obligations in respect of transportation of goods. Contracts should use internationally recognised terms as laid down by the International Chamber of Commerce.

The rewards of internationalisation can be high but as with all new business, carry risk and opportunity. The only way to mitigate risk is to build process and awareness into every stage.

______________

Press contact

Dominique Maeremans, business development/marketing manager

Tel: +44 20 7767 2621

E-mail: d.maeremans@uhy.com